Lives saved

7

Boating

Ocean

Boat Sinking

Thunder storm

Honolulu HI

21.3069444°N, -157.8583333°W

Posted on May 3, 2018 by Zachary Denzer

What happened?

It was a half hour past midnight when we noticed the boat was filling up. We had heard water sloshing around in the cabin, and when we shined our flashlights below, it was already about eighteen inches deep. We fumbled for a few minutes trying to manually remove the water with the hand-operated bilge pump, but we soon realized this was no ordinary leak.It was blowing 18 knots with five foot seas in the middle of the Kauai channel, and our ship was sinking.

Kenith Scott was on the helm at the time, and he immediately told everyone to unclip from the safety harnesses that attached us to the boat. Zach Denzer, who’s dad Mark owned the boat, dashed below to get life jackets and the radio. He got on channel 16 to notify the Coast Guard that we were taking on water, and also activated our Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB) while the rest of the crew dawned life jackets. Zach then grabbed a bucket and began bailing the water out of the cabin. I took the helm from Kenith, who joined Zach below. They bailed for several minutes, but the water was coming in faster than they could empty it. I shined my flashlight into the pitch black cabin to aid their efforts. Random pieces of gear were floating in the water, which was now up to their knees.

Abandoning the thought of isolating the source of the leak, our situation had become frantic. We called in the May Day. Jamile Qureshi, a merchant marine who we brought aboard as our navigator, handled the radio communication with the Coast Guard. He had the littlest sailing experience of the entire crew, as this was his first major racing venture. Despite his lack of actual sailing experience, he demonstrated his maritime ability as he deftly handled the radio communication with the Coast Guard, staying in constant contact, using the hand held GPS to update them with our exact coordinates every ten minutes or so.

There was also a second, personal EPIRB, which we activated and wrapped around the wrist of Bree Nidds, one of the two female members of our crew. Tate Wester began shooting off flares, which sparked upon ignition, but failed to light up the night sky. There was a forty-footer about ten miles ahead of us, and if we were able to signal them, maybe they could assist us. Yet the sky remained dark as our flares failed, and we knew our sole hope was a Coast Guard rescue.

Despite the intensity of the situation-the swell beating at the side of the boat, the failing flares, the water rising in the bottom of the cockpit, the steady communication with the Coast Guard kept us fairly collected. There was some initial panic when we realized we were sinking in the middle of the channel, but we clung to each radio transmission, a sure sign that we were going to be alright. In the meantime, I trimmed the mainsail to keep us into the wind. The boat was filling up fast now and the last thing we wanted was a capsize. We all agreed that if we ended up having to ditch the boat, it would be pivotal to stay together. We readied lines to tie to each other, and gathered the most important gear. We had two EPIRBS, a hand-held VHF radio, a hand-held GPS, a strobe-light, a bag of life jackets to hold on to, and a large water cooler with several waters and Gatorades. It didn’t even cross our minds to salvage cell phones or wallets-mere trifles in such a circumstance.

By now the crew members had taken shifts down below bailing out water, and eventually getting sea-sick. I tried to steady the boat, but as we sank lower and lower, the steering became more unstable. Water began to flood over the transom and into the cabin. Quite honestly, I was in a daze most of the time, as I had already thrown up from sea sickness before the boat even began to sink. But there was a moment when I looked away from the crew, over my shoulder at the black ocean and the waves lapping and asked myself if this would be the way it all would end. I kept this to myself, and was brought back to the crew by the voice of Kenith, who assured us to all stay calm, as the Coast Guard had just deployed a rescue helicopter from Barber’s Point on Oahu.

By now waves were crashing directly into the cabin, and we knew the boat was going down fast. When the side stays were underwater, we all dipped off the transom, kicking ourselves as far away from the boat as possible. We watched it drift away from us. It sank straight down, never leaning to one side or the other. The water was over the entire cabin top, and eventually the spreaders, until all that was left was the mast-head-light glistening against the black night sky. It dipped down below the surface, and we were left in complete darkness, huddled together in the middle of the ocean, thirty miles away from land.

From here, minutes went by like hours. Jamile notified the Coast Guard that the ship had sank, and that we were now adrift at sea. He was still able to relay our coordinates, holding the VHF and GPS above the water. They told us it would be about a half hour before they would reach us. All we could do was wait. Every little light in the sky seemed like rescue. We saw planes, shooting stars, distant lights from shore, all of which raised our hopes to the highest exaltation, only to let us plummet down as the helicopter failed to materialize. At this point, Kenith, a veteran of the Iraq War, said something I will never forget. “Man, I fought a war, and this is about the hairiest situation I have ever been in.”

We all said a little prayer to ourselves, trying to fight off the thought of sharks, or whether or not the helicopter would find us, and just clung to each other, waiting. About twenty minutes later we saw a headlight on the horizon. It was coming towards us. We heard the thunder from the helicopter blades low over the water. A Coast Guard chopper flew directly overhead, shining their search light down on us, and eventually even passing us. There was a little panic as we thought they had missed us. Jamile even radioed in to tell them, but the Coast Guard station assured us that we had been spotted, and the helicopter was just making an approach on our position.

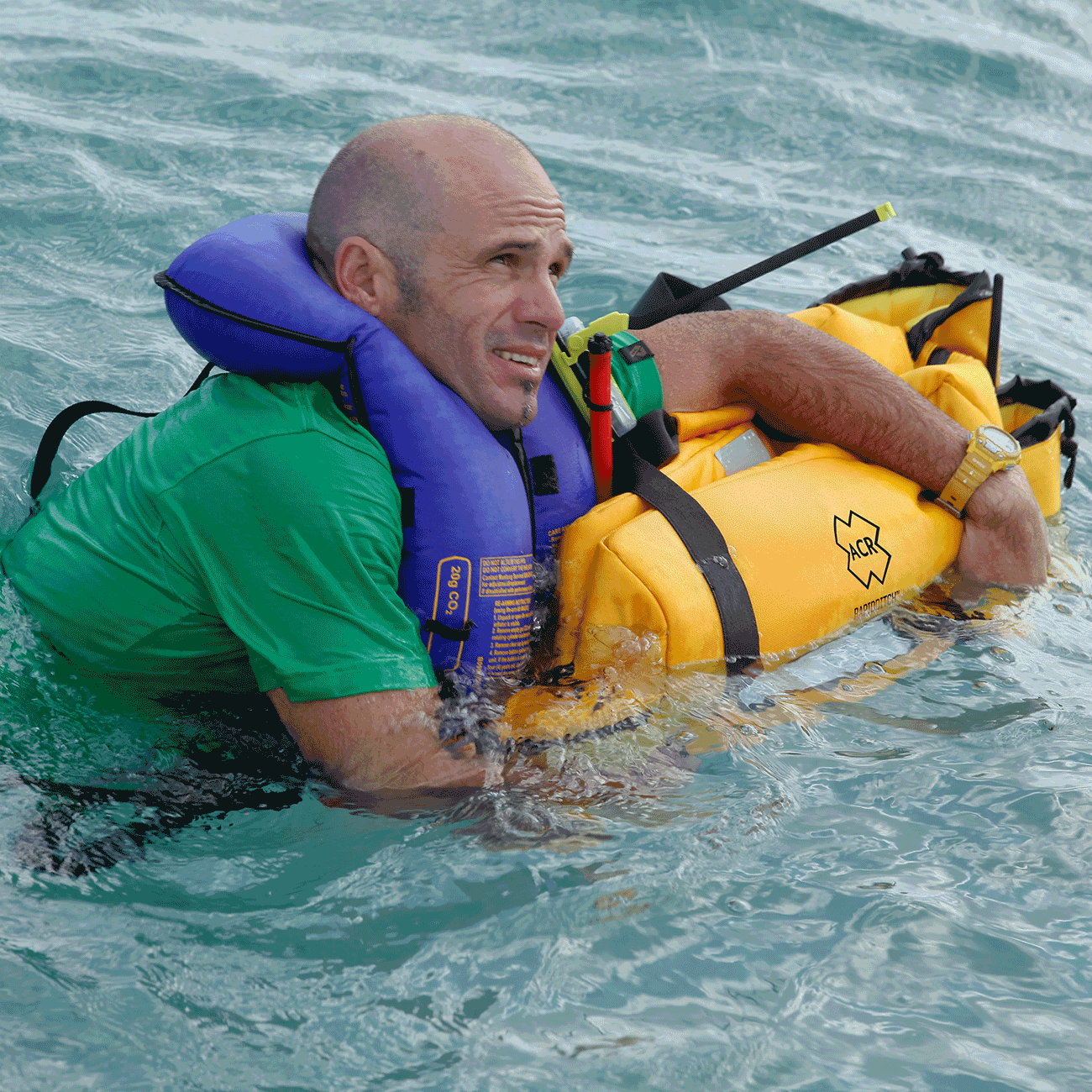

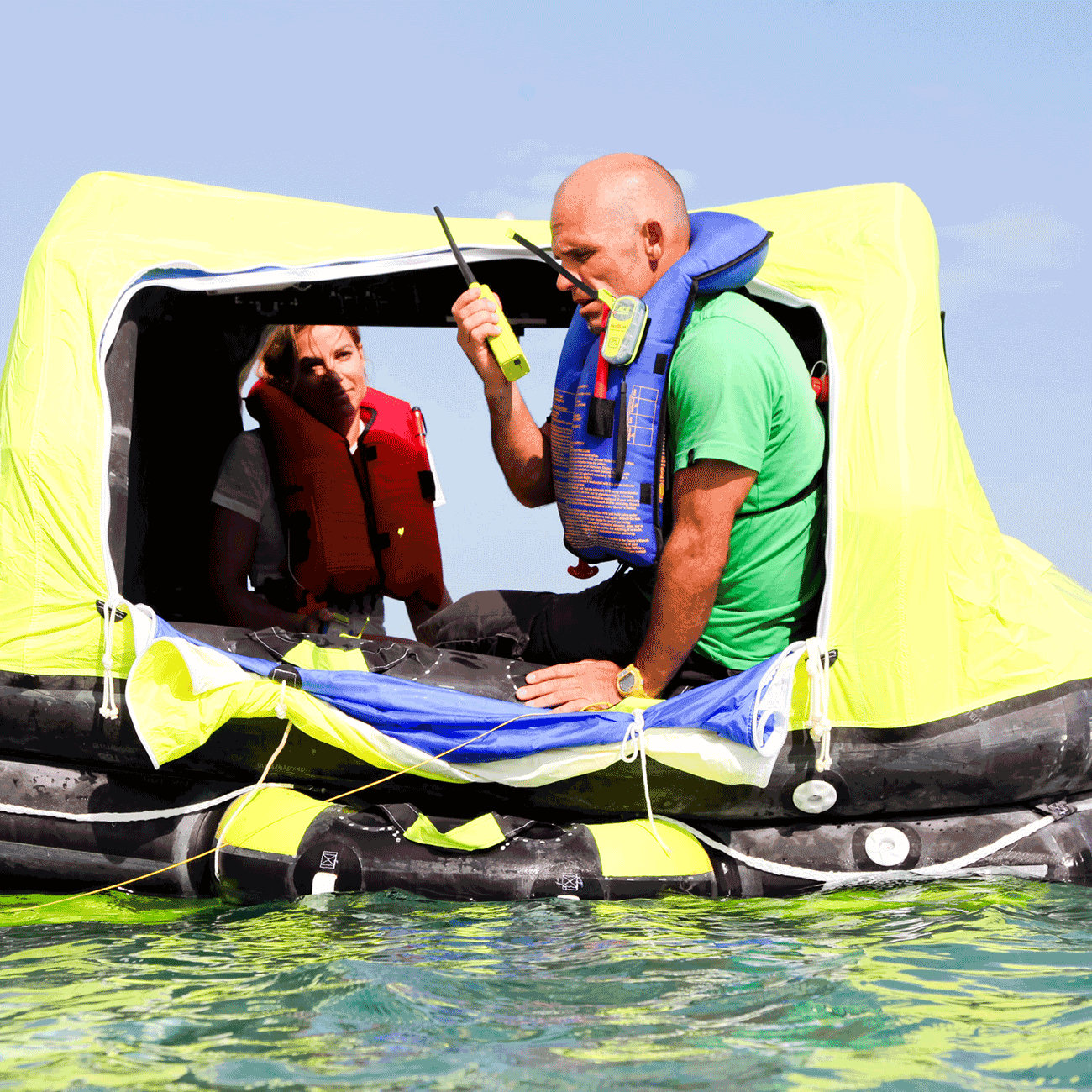

Minutes later the chopper approached from leeward, deploying a rescue swimmer. I wanted to watch every move they made, but the water from the blades shot up from the waves like needles. The diver swam up to us, asking if anyone was injured, assessing the state of each member of the crew. At this point I became sick again, though the fact that we were being rescued should have revitalized me, I was dry-heaving when the diver swam up to us. He told us that four of us were to be airlifted out on the helicopter, while three would have to stay back in a life raft. First to be airlifted was Lani Johnson, the other female member of our crew, then myself, as I was in probably the roughest shape of anyone, then Bree, and then Tate. The rescue swimmer brought me over to the dangling rescue cage, placed me in, and told me to sit on my hands to keep them from banging against the helicopter. I was winched up to safety, swaying back and froth in the wind as the cage rose higher. One of the crew members brought me into the cabin where Lani awaited. We immediately hugged and watched the cage go back down for Bree, and then again for Tate.

They deployed a life raft for the three other members of our crew and the rescue swimmer. From the helicopter, I could see the strobe light bouncing around in the waves below. With the life-raft deployed we turned around and headed for Lihue. I sat by the window and looked up at the stars over the ocean. I looked at the faces of the members of our crew, all of us in shock. And as much as I wanted to tell them how much I cared for them and how glad I was to be alive, the motor from the helicopter drowned out any form of verbal communication. That was the loneliest part of the night for me, being so close to my friends, but unable to tell them how happy I was that we made it through.

Eventually we landed back on Kauai, where we were escorted to the fire station, and eventually to the Coast Guard station where we met up with the other three members of our crew. After some logistical issues of not being able to buy flights or board the planes without identification or proper foot wear, we made it back to Oahu on an afternoon flight. We were met with T.V. cameras and reporters at the airport. We smiled for the cameras and took our interviews, watching every day people walk by on the way to their flights, some staring at us awkwardly, others oblivious.

Days earlier, our crew was briefed by Zach’s dad on all of the safety equipment on the boat. He showed us how to operate the two EPIRBS, the VHF, the GPS, the life jackets and safety harnesses. All of the batteries were replaced in our equipment, new rigging was put on the boat, all the screws were tightened and every piece of gear accounted for. We were as prepared as we could have been for what we went through, and though it never crossed our minds that we might have to abandon ship, I am proud of every member of the crew for how they handled the situation. Bree Nidds is 20 years old. I am 21. Tate Wester is 22. Lani Johnson and Zach Denzer are 23. Kenith Scott is 26, and Jamile Qureshi is 35. We were by far the youngest crew sailing back that night, but no one freaked out, everyone stuck together, and we made it through the night.

I have learned many things from racing sailboats. I have learned how to make decisions, prioritize my actions, adapt to shifts both on the water and in my life. I have learned that sometimes you’re up and other times you’re down, and it is always crucial to focus on the task at hand. I have never in my experience, however, thought that sailing would teach me to cope with the threat of death. There is nothing that can prepare you for that. And had our EPIRB’s failed, or had our VHF batteries been dead, it could have been a very different story. The steps you take to prepare yourself for a sailing venture, however threatening or non threatening you think it may be, could very well save your life when a situation becomes dire. As long as you don’t let that situation get away from you, and remain confident in the steps you have taken to prepare, nothing should stop you from casting off and sailing into that horizon.

Words of wisdom

The steps you take to prepare yourself for a sailing venture, however threatening or non threatening you think it may be, could very well save your life when a situation becomes dire.

Thank you note

Thank you ACR!

Rescue location

Honolulu HI

Rescue team

Coast Guard

ResQLink™

Go to product detailsOut of stock