Lives saved

4

Fishing

Ocean

Weather

Rogue wave

Catalina Island

33.3878856°N, -118.4163103°W

Posted on May 3, 2018 by Foster

What happened?

Except for the cold, the evening was perfect for a quick ride over to Catalina Island to dive for lobsters. We were all wearing ski clothes, which kept us warm in the 38-degree air. The water temperature was a chilly 58-degrees, but we would be using thick wetsuits during the dive. I was with my three friends Robert Welch, Tony Kettering, and Greg Cullen.

We were cruising along enjoying the ride when suddenly I felt like someone hit me in the face with a baseball bat. I felt most of the force of impact in my eye sockets, and when conscious thought returned after a few seconds, I found myself staring straight ahead in my original posture, with one hand on the steering wheel and the other on the throttle. Tons of water had swept over the bow, shattering the windshield and flooding the deck. I really had no idea what had just happened. I asked Robert if he had been hit as well and he responded, “Yeah, but not as bad as you.” He immediately sprang into action and told me to turn the boat around so that the bow would be facing into the waves. When I finally looked down, I saw that we were standing knee-deep in swirling water, illuminated to an eerie green color by the submerged deck lights. I heard Tony tell me to turn the bilge pump on, which I immediately proceeded to do.

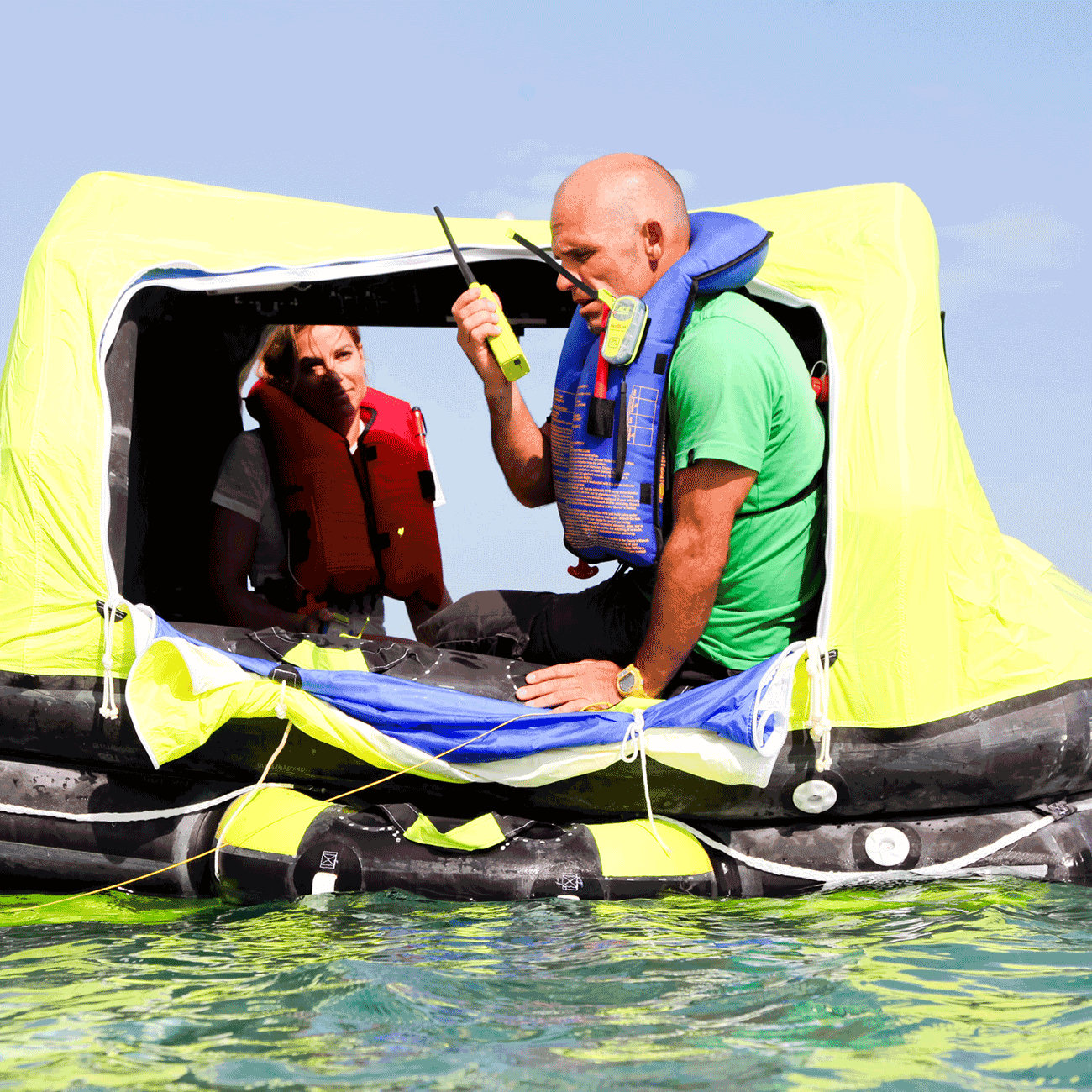

Foster _Stanback _LocationThen I heard Robert say “This is serious, guys. Foster, get the Personal Locator Beacon ready.” Before removing the ACR ResQLink PLB from my life jacket, I decided to grab my wetsuit bag from under the bow compartment, as the window of opportunity for doing so was quickly closing. Once I had retrieved it, I unzipped the pocket in the front of my life jacket with my other hand and pulled out the small electronic device that would supposedly send our position to the Coast Guard. I still couldn’t believe it had come to this. Deep down I was hoping that somehow we might be able to recover on our own. I asked Robert if I should go ahead and turn on the PLB. Without hesitation he responded, “Yes.”

I pushed the large rubber button and the built in strobe light began flashing, indicating that a distress call and our GPS coordinates were now being relayed to the Coast Guard. I knew the engine compartment was filling up with water faster than the bilge pump could remove it. The weight of all that water combined with the massive engine was pulling the stern under the waves. It was hopeless. The unimaginable was happening. We were going to sink.

I immediately told the guys to grab their wetsuits. A few seconds later water poured over the stern and the bow began to pitch upward sharply. As our footing disappeared beneath us, I said “Here we go” and we all stepped off into the freezing ocean. I expected more of a shock from hitting the cold water, but initially it wasn’t so bad. The Mustang Survival flotation jacket I had on worked pretty well. I took one last look at the boat before reaching behind my back for the VHF GMDSS Survival Craft Radio that I had placed in a belt pack strapped around my waist. About five feet of the bow were sticking straight out of the water. Four feet…three feet… I stopped looking so I could focus on sending out a distress call on the radio.

My friends watched the boat go completely under. For some strange reason the navigation lights stayed on as it sank into the depths, giving it a ghostly appearance as it made its long journey to the underworld. Some four hundred fathoms below, it would eventually find its resting place on the ocean floor, never to see the light of day again. It was a sad end for a vessel that had spent so many days dancing along the waves in the sun. But we had no intention of joining it, we were still on the surface and, thankfully, still alive.

A few years before I had taken some wilderness survival courses with an instructor named Cody Lundin, he pointed out that in a real survival situation fine motor skills would degrade to the point that even the simplest of tasks-such as striking a match-could become extremely difficult or even impossible. He said that any gear we brought along should be very simple to use and that we should actually practice with it beforehand.

Fortunately, the ACR ResQLink personal locator beacon was easy to activate. There were only two rubber buttons-one to test the device to make sure it was working and the other to activate it. Fortunately, I followed Cody’s advice and became familiar with it in the comfort of my home office. Unfortunately, I did not do the same with the VHF Survival Craft radio. When I finally managed to get the radio out of my belt pack and up in front of my face, I couldn’t see anything-and I didn’t have a flashlight (another very important piece of survival gear). I grabbed the rubber bands and ripped them off forcefully- the plastic cover plates were quickly dislodged, but so was the battery (something I wouldn’t learn until much later). Sea water flowed around the two metal contacts, rapidly drawing away the precious electricity needed to power the device. I slid the side button upwards and to my great relief the face of the radio suddenly lit up. I was even more relieved to see that it was already set on Channel 16-the channel reserved for emergency broadcasts at sea. Thanks to the well-conceived design of this radio, I was still able to operate it in a crisis situation without any prior practice.

I immediately pressed the lighted “TRANSMIT” button and called out, “MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY. Our boat has sunk about four miles to the east of Catalina. We have four men in the water.” I was elated when, over a great deal of static, I heard the garbled response, “San Diego Base, Say Again.” I pushed the transmit button again, and repeated, “MAYDAY, MAYDAY, MAYDAY. Four boaters in the water off Catalina.” No response. I looked at the radio again. It was completely dark. I frantically started moving the ON/OFF switch up and town and pushing the TRANSMIT button. The radio flickered on and off a couple more times and then went completely dead. I was devastated.

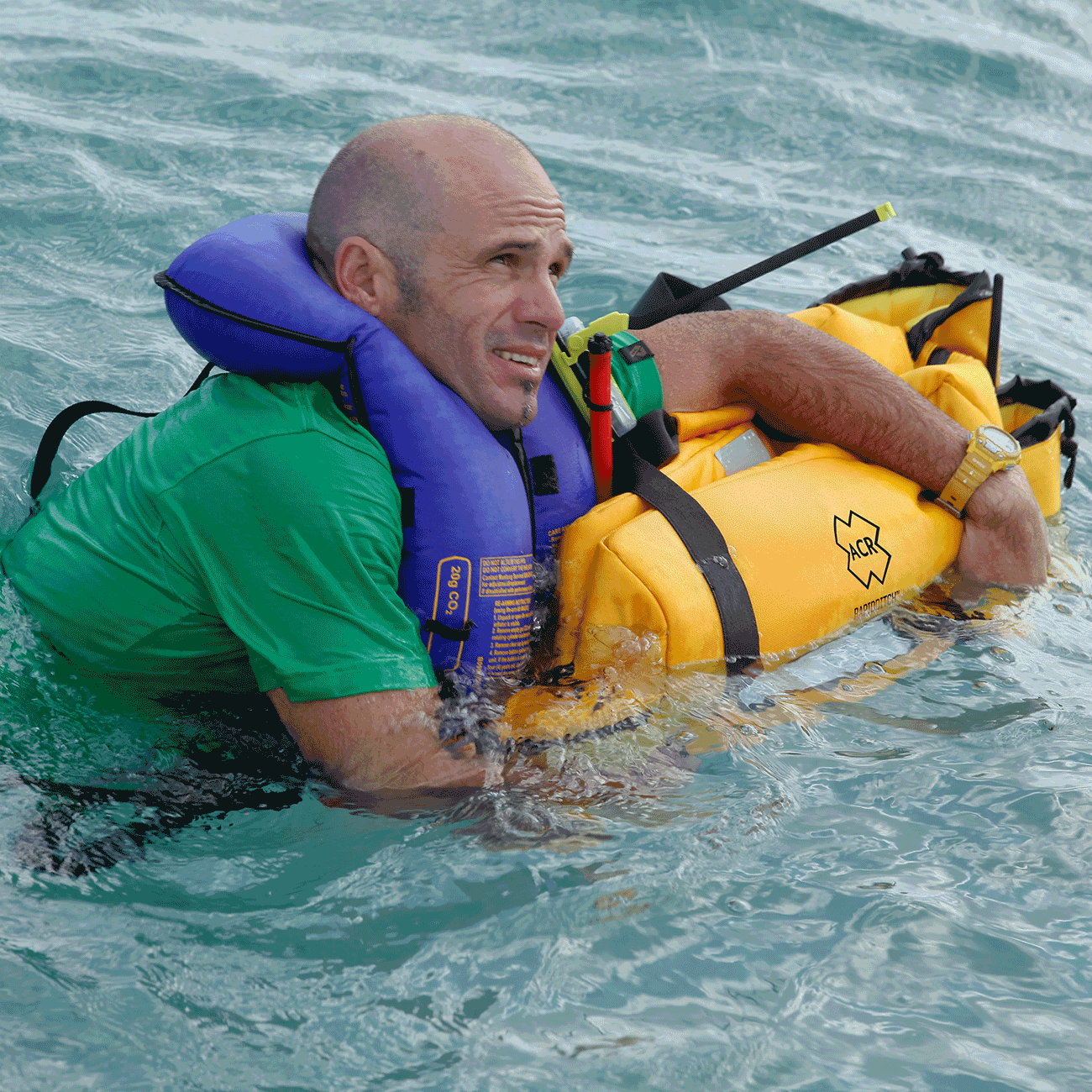

Fortunately, we still had the ResQLink PLB, but it couldn’t talk to us and tell us that it was working and that help was on the way. Yet it was all we had left. I could only take comfort in the steady blinking of the strobe light and hope that it was sending our GPS coordinates to a satellite far overhead and letting someone, somewhere know that we needed help, that we only had a few hours left before hypothermia would cause all of us to drift into unconsciousness and ultimately drown when we could no longer hold our heads above the windswept waves. I had been holding the ResQLink in my hand ever since I stepped off the edge of our sinking boat. Since it didn’t float, I was clinching it tightly with my left hand while I held the radio in my right hand. Although the radio was no longer working, I was reluctant to toss it aside just in case it decided to come back to life.

My wetsuit was packed in a small nylon duffle bag. I had slipped my right arm through the handles so it was secure as long as I held onto the radio. But there was no way to unzip the bag, pull out the suit and put it on unless I could free up both hands. I told the guys to get their wetsuits on and when they were finished, I would hand the ResQLink and radio to one of them so that I could do the same. It would be a long wait. Putting on a tight neoprene wetsuit is hard enough when you are standing on the deck of a boat that is rocking back and forth. But at least you have a solid footing and can grab onto something for support.

By now the wind was starting to pick up and the waves were getting larger. We had to continually hold our breath and shut our eyes as they swept over our heads. We were also starting to drift apart. Greg had a diving flashlight that he could use to signal our position, and I had the strobe light on the ResQLink that was steadily flashing. A strobe light can be visible for 15 miles on a clear night. Yet if we became separated, Tony and Robert would disappear in the darkness. Even with night vision goggles, it would have been difficult for the Coast Guard to find them in such a vast expanse of ocean. Robert, who had fallen behind us while putting on his wetsuit, was now out in front. He had started swimming toward the flashing red beacon on the cliffs at Catalina. When making preparations for an inherently risky sea voyage, ignorance is your worst enemy, but once you’re facing imminent death it can become your greatest friend.

On the ocean at night, there is really no good way to judge distance. A flashing beacon or the navigation lights of an approaching boat might be a mile away or a hundred yards away. I had assumed we were about 4-5 miles from the island. I was way off. We were really 10 miles from shore-exactly in the middle of the channel and as far from land in either direction as we could possibly be. There was no way we were going to swim back to Newport Harbor with large waves and 20 knot winds pushing against us. But making it to shore on Catalina seemed possible, if the cold didn’t kill us before we got there. I said, “Guys, if people can swim across the English Channel without wetsuits then we can make it to Catalina.” Ignorance is bliss. At this point, we still hadn’t given up the hope of being rescued, though everyone was starting to have doubts.

USCG-ChopperA noise in the distance brought my actions to a sudden halt. I could clearly hear the sound of helicopter rotors. After a few seconds, I could tell that it was getting closer and that it was flying near the surface of the ocean. Then I spotted the flashing navigation beacons. It was headed straight toward us! Within a minute we could see the silhouette of the Coast Guard rescue chopper against the clear, moonlit sky. I called out to Greg and told him to turn the diving light on and off in patterns of three flashes-a standard SOS signal. I stretched out my arm and aimed the strobe light of the ResQLink directly at the approaching aircraft. The helicopter continued toward us until it was directly overhead, about a hundred feet above the water. We expected to see a spotlight and hear a loudspeaker announce that they would be lowering a basket or harness. Instead, the helicopter kept flying straight ahead. I heard Tony yell out, “Where are they going?” Greg continued to flash the light at them, while I kept trying to extend my arm further to somehow make the strobe light more visible. I even turned my hand around and aimed it at my face to make sure I had been aiming the light in the right direction and that my palm had not been covering up the bulb. Since they had flown right over us at such a low altitude I was not too worried. The helicopter continued on its course for a few hundred more yards and then stopped, hovering in place for a few minutes. Eventually it came back around and shined the spotlight on us. To avoid hitting us with the prop blast it remained about fifty yards away. We could then see the opening in the side and a rescue basket being lowered. Words cannot describe the elation we all felt at that moment.

A rescue swimmer jumped into the ocean and Greg quickly swam over to meet him. He needed to be the first one out of the water, as the long ordeal of getting his wetsuit on had exhausted him and chilled him down considerably. Tony, Robert, and I remained close together, laughing and talking about what a cool experience this was. Tony commented, “This is just like in the movies.” Tony went up next, then Robert. Finally, the rescue swimmer came over to me and started to tell me what I needed to do as I went up in the basket. Then he stopped and said that the boat had arrived and that I would no longer need to go up in the helicopter. I turned around and saw flashing blue lights all around me. There were four ships surrounding the area, including an 85-foot Coast Guard Cutter.

A 45-foot rescue vessel approached and the crew pulled me aboard. One of the officers led me to a warm room below deck and gave me some blankets to wrap up in. After checking me out to make sure I was OK, he asked for details about what happened. It took slightly less than an hour to get back to the Coast Guard station in San Pedro. When I arrived they told me that the base commander wanted to talk to me. I thought, “Oh no, here we go. He’s going to chew me out for sinking a boat and involving dozens of people in an expensive rescue operation.” Soon a smiling young man came out and listened attentively as I divulged all the details of our ordeal. When I was finished, he said, “Well, we just want to thank you for making our job a whole lot easier.” My three friends, who were taken further north to the air station at LAX, asked the rescue swimmer how often he had had to go out at night on rescue operations. He replied that, surprisingly, such missions were quite common, but we were the first actual “survivors” he had pulled out of the water in seven years. People typically lose consciousness in 1 to 2 hours in 50-60 degree water. Our wetsuits would perhaps have given us a few more hours, but there was no way we would have made the ten mile swim to the shore of Catalina.

The only things that saved us were the ACR Survival Craft Radio and the ResQLink personal locator beacon. Yes, even the radio still did its job after I had dislodged the battery, thanks to an amazing new system developed by the Coast Guard called Rescue 21. Any distress call on the emergency channel is picked up by various receiving towers and immediately recorded on a computer. A program then calculates the exact coordinates of the source of the transmission using triangulation. The Coast Guard personnel were able to pinpoint exactly where we were when I made our brief May Day call. They then overlaid the position being reported by the ResQLink and got a perfect match. Thanks to these amazing electronic devices and the dedication and professionalism of the Coast Guard, we were the lucky participants in a “textbook rescue.”

Words of wisdom

Any gear we brought along should be very simple to use and that we should actually practice with it beforehand.

Thank you note

Thank you ACR!

Rescue location

Catalina Island

Rescue team

Coast Guard

ResQLink™

Go to product detailsOut of stock